An architect looking to create a home that forms a deep connection with its surroundings could do worse than to start with a parcel of land in northwest Montana that its owners once used as a campsite.

That was the inspiration and opportunity for Tom Kundig, the Seattle-based architect whose firm, Olson Kundig, is known for modernist designs that blend seamlessly with the environment. This vacation home, called Dragonfly, was inspired by that insect in the way that it blends in with its natural habitat and sits lightly on the land. The project includes retractable window walls to maximize natural ventilation, a broad, overhanging roof to prevent overheating, and reclaimed-wood siding, along with a landscape filled with native plants and green roofs.

“My approach to design prioritizes the honest use of materials and techniques and celebrates the craft of how things go together,” Kundig says. “This means selecting materials that are durable and low-maintenance and using what we need while reducing waste. I try to design living, breathing buildings that open to the climate, harvest natural daylight, and make a connection to their surroundings.”

Here, Kundig—whose book Tom Kundig: Working Title is coming out this June—shares his sustainable approach to design.

ELLE Decor: Can you describe the sustainable design elements you incorporated into this Montana retreat?

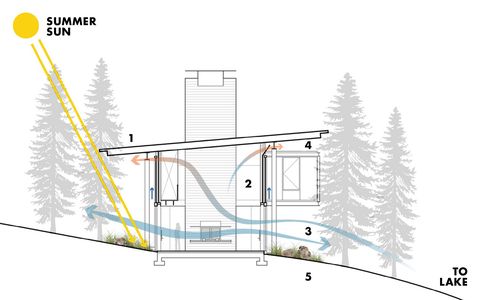

Tom Kundig: Dragonfly was designed to work with the climate and naturally occurring opportunities for passive conditioning. The home is situated so that it can take advantage of natural breezes coming off the lake, and the manually retractable guillotine window walls in the main living area maximize these opportunities for natural ventilation. Windows on the upper levels pull out warm air in the summer, and the home’s broad overhangs provide shading to protect the home from overheating. In the winter, south-facing glazing allows for maximal solar heat gain. We used reclaimed-wood siding, native landscaping, and planted roofs on the home’s auxiliary buildings to further reduce its impact on the site.

ED: What were some of your priorities with the Dragonfly project?

TK: At its heart, this vacation house is about creating a place where a young family can gather away from the city to enjoy the outdoors and build a legacy of memories. The property was a longtime vacation spot for the family, who camped there before their home was built. The home is designed to maintain the sense of natural discovery the family enjoyed when spending time on the undeveloped land.

ED: What are some of your favorite elements of this project?

TK: As with all of my residential projects, my absolute favorite part is knowing that the clients and their family will enjoy this property together for many years to come. The clients envisioned this home as a very special touchstone in their family and a place to spend time together. Dragonfly is a place their children will someday share with their own kids.

I also like the way it celebrates the eco-tone condition between forest, lake, and meadow. Dragonfly emphasizes the crossing point between these ecological zones while sitting very lightly on the land. We worked hard to get the siting of the home just right, and being out there and feeling how well it fits on the land—it’s like music.

I really enjoy the way the house can “dress” for the climate and be used during all four seasons. The large guillotine doors allow Dragonfly to transition from a protected refuge to a semi-enclosed condition, and then be exposed and open to the lake.

ED: Do you have any favorite eco-friendly materials that you like to work with?

TK: I’m interested in design that expresses the tectonics of materials—that showcases how things go together instead of covering it up. I select materials that will weather over time and embrace their natural patina, rather than using additional chemicals or treatments that fight against what the materials want to do.

I’m especially interested in dwellings that encourage users to engage with their surroundings. I like to use kinetic building elements that allow people to physically move pieces of the building, like opening or closing windows, walls, and shutters. When a user takes hold of a wheel and turns it, opening up some aspect of a building, the effect is not only physical and tactile but emotional as well. Removing barriers between indoor and outdoor spaces allows users to fully experience the surrounding environment on a deeper level. Deeply engaging all of your senses promotes a kind of mindfulness about how you take up space, which in turn promotes a sense of stewardship of your environment.

ED: But how do you design a building so that it melds seamlessly into that environment?

TK: I always say that architecture is the exterior context pushing against the interior context. It’s the membrane between those two; the push and pull between those two agendas. That could be a natural context—views and a landscape—or it could be an urban context with a city street and a dense built environment. In either context, I try to design living, breathing buildings that open to the climate, harvest natural daylight, and make a connection to their surroundings.

ED: Are you finding that sustainable design is also important to your clients?

TK: It’s top of mind for a lot of our clients across all types of projects, from residential work that’s all about a light touch on a very sensitive environment to cultural work like the new Burke Museum for natural history and culture in Seattle. When we’re designing something that’s going to sit in a landscape that is special and loved by our clients—whether urban or rural or in between—they want to respect and honor that environment. A lot of our clients are interested in improving the performance of the building. They’re looking for ways the building can be more economical in its energy and water use, even generating its own energy or recycling water on-site.

My clients are increasingly interested in passive design and natural ventilation systems, which also happen to be great ways to connect people to place. I see great potential here for long-term cultural change, as the success of these systems depend on the building, the local climate, and the users.

ED: Are you trying to make your work even more sustainable nowadays?

TK: We’re working on a number of tools that our project teams can use to make informed decisions about where to focus their efforts early in the design process. One of these tools is a dashboard that examines both embodied and operational carbon over the lifetime of a building. Ultimately, it will help everyone understand the impact of design decisions and push us to create better, more interesting work.

We know it’s more sustainable to adapt an existing building rather than tear it down and build new. I’m really excited by the design challenge of finding inspiration in “ugly” buildings that are typically unloved—old shopping malls, office parks. There are so many more bad buildings out there than good buildings. I think that’s the future.

ED: Tell us about your new book.

TK: It includes 29 recent projects from around the world, both public and private, including residences, hospitality projects, cultural spaces, and workplaces. It’s a diverse mix of work, but it highlights the ongoing exploration of contextual design, materiality, and craft that has defined my career. People associate my work with houses, but this book also shows the nonresidential projects I design, including Martin’s Lane Winery in British Columbia, the Burke Museum, 100 Stewart Hotel & Apartments in Seattle, and Tillamook Creamery in Oregon.

ED: How is the design industry as a whole doing in regards to sustainable design?

TK: Overall, I think the industry recognizes the role we can play in addressing the current climate crisis. Energy codes are getting tougher, and buildings are being asked to perform better. Lately, the conversation about sustainable design has expanded to consider the impact of carbon throughout the life span of a building, including carbon associated with the extraction and manufacture of building materials, construction, operation, and eventually deconstruction.

ED: Is there one thing designers and architects everywhere should do to create more sustainable living spaces?

TK: The most important thing architects can do is design buildings that people love. Once you have that connection to a building, you want to save it, and you want to keep it around instead of tearing it down. That’s a big reason I think it’s so important to foster connections with the natural environment. Creating those connections makes the case that these resources are vital to our lives—that protecting them is important. Engaging the climate and incorporating passive conditioning further underscores that relationship and helps people feel a sense of responsibility for the world around them.

More Stories

Buying a Condo

Red, White and Blue – What Are The Timeshare Seasons?

What You Need to Know About Selling Your Condominium in Today’s Market